A 529 plan can be an effective estate planning tool. But because many families are unaware of its benefits, very few consider using a 529 plan for estate planning.

Nevertheless, families may need to consider including 529 plans as part of their estate plans because of potential changes to death taxes.

We explain why in more detail below and break down all the "how-tos" of using a 529 plan for estate planning. Here's what you need to know.

Possible Changes To Death Taxes

In 2024, the unified lifetime gift, estate and generation-skipping transfer tax exemption is $13.6 million ($27.2 million for married couples), up from $5.49 million in 2017.

Since 2010, the lifetime exemption has been portable between spouses, allowing a surviving spouse to get the unused portion of their spouse’s lifetime exemption. This effectively provides a married couple with twice the lifetime exemption of a single person. The deceased spouse must have been a U.S. citizen at the time of death. The surviving spouse must elect portability when they file a timely Federal Estate Tax Return, IRS Form 706, for the deceased spouse. IRS Form 706 must be filed within 9 months plus extensions after the date of the decedent’s death. IRS Form 4768 may be filed to claim an automatic 6-month extension.

However, the future of the exemption from death taxes is uncertain. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 doubled the lifetime exemption. But this increase will sunset for tax years after 2025 unless Congress acts to extend it. The lifetime exemption will revert back to $5 million plus an inflation adjustment for taxpayers who die in 2026 and later years.

In addition, President Biden has proposed cutting the lifetime exemptions to $3.5 million for estates and $1 million for gifts (returning to the exemptions that were in effect in 2009). His proposal also calls for increasing the tax rate, which is currently 40%. He has also proposed eliminating the stepped-up basis for inherited assets and to tax the unrealized capital gains at ordinary income tax rates (as opposed to long-term capital gains tax rates).

Although President Biden did not include the proposed decreases in the lifetime exemptions in the American Families Plan, these cuts might be included in future legislation.

Opposition To Estate Tax Changes

These proposals have generated bipartisan opposition from lawmakers for several reasons:

The proposed changes also generate relatively little tax revenue. Fewer than 2,000 families pay federal estate taxes each year, yielding less than $20 billion in tax revenue.

States That Levy Estate Taxes

State estate and inheritance taxes, which vary by state, may have lower exemptions than the federal levels, causing smaller estates to be taxed. Families may wish to use 529 plans to reduce state estate and inheritance taxes in these states.

Currently, 13 states have state estate taxes: Connecticut, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington. The state estate tax exemption is $1 million in Massachusetts.

As of writing, 6 states have state inheritance taxes: Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania includes out-of-state 529 plans in the account owner’s estate, but not in-state 529 plans.

Inheritance taxes may depend on the relationship of the heir to the decedent. In Pennsylvania, for example, the inheritance tax rate is 0% for surviving spouses or parents of a minor child, 4.5% for direct descendants, 12% for siblings, and 15% to other heirs (except for charitable organizations, exempt institutions and government entities that are exempt from tax).

Benefits Of Using A 529 Plan For Estate Planning

The advantages of using 529 plans for estate planning involve contributions, distributions, control and financial aid impact. They're simpler, easier to use and less expensive to set up than complicated trusts. They also have generous and flexible contribution limits. There are no income, age or time limits.

Account owners retain control over the 529 plan account and can change the beneficiary. Earnings accumulate on a tax-deferred basis and distributions are tax-free if used to pay for qualified educational expenses. Grandparents can also use 529 plans to leave a legacy for their descendants. And policymakers are unlikely to limit these estate-planning benefits.

Contributions

Contributions are removed from the contributor’s estate for federal estate tax purposes. Contributions are considered to be a completed gift.

Although there is no annual contribution limit for 529 plans, contributors can give up to the annual gift tax exclusion, which is $18,000 per year in 2024, without incurring gift taxes or using up part of the lifetime gift tax exemption.

There are no gift tax limits if the beneficiary is the account owner or the account owner’s spouse. The spouse must be a U.S. citizen. If the spouse is not a U.S. citizen, the gifts are capped at $157,000 a year, as of 2000.

If the beneficiary is a grandchild, contributions may result in generation-skipping transfer taxes, but the annual and lifetime exemptions and tax rates are the same as for gift and estate taxes. Generation-skipping transfer taxes apply if the beneficiary is two or more generations younger than the contributor or if the beneficiary is at least 37.5 years younger than the contributor. There is an exception if the grandchild’s parents are deceased at the time of the transfer.

Superfunding

Five-year gift-tax averaging, also known as superfunding, allows a contributor to make a lump sum contribution of up to five times the annual gift tax exclusion and have it treated as through it occurs over a five-year period.

The contributor may be unable to make additional gifts to the beneficiary during the five-year period, unless the prorated gift is less than the annual gift tax exclusion amount. If the contributor dies during the 5-year period, part of the contribution may be included in the contributor’s estate.

For example, if the contributor dies in year 3, the remaining 2 years of contributions will be included in the contributor’s estate. The contributor may need to file IRS Form 709 to report the contribution, even if there are no gift taxes or reduction in the lifetime exemption.

State Limits And Benefits

There are high aggregate contribution limits, which vary by state, ranging from $235,000 in Georgia and Mississippi to $542,000 in New Hampshire. Once the account balance reaches the aggregate limit, no more contributions are permitted, but the earnings may continue to accumulate.

Families may be able to bypass the state’s aggregate contribution limits by opening 529 plans in multiple states. But contributors will still be subject to the annual gift tax exclusion limits.

Contributions are eligible for a state income tax deduction or tax credit on state income tax returns in two-thirds of the states. The amount of the state income tax break varies by state. There are no income limits, age limits or time limits on contributions. The beneficiary does not need to be of college age and can already have a college degree.

Distributions

Earnings in a 529 plan accumulate on a tax-deferred basis. And distributions are tax-free if used for qualified educational expenses. The money can be used to pay for elementary and secondary school tuition, college costs, graduate or professional school costs, and continuing education.

Non-qualified distributions are subject to ordinary income taxes at the recipient’s tax rate and a 10% tax penalty. The penalty is only levied on the earnings portion of the distribution, not the full amount of the distribution.

Non-qualified distributions are not subject to capital gains taxes, gift taxes or estate taxes. If the contributor previously claimed a state income tax deduction or tax credit, the state income tax break may be subject to recapture if the account owner makes a non-qualified distribution.

There are no income limits, age limits or time limits on distributions. Account owners are not required to make distributions when the beneficiary reaches a particular age. They can choose to leave the money in the account, letting it continue to accumulate earnings.

Control

The account owner retains control over the 529 plan account, unlike direct gifts to the beneficiary or complicated trust funds. The account does not transfer to the beneficiary when the beneficiary reaches a particular age. Instead, the account owner gets to decide whether and when to make distributions.

The account owner can change the beneficiary to a member of the beneficiary’s family, including to the account owner. This effectively lets the account owner revoke the gift, if they choose, by changing the beneficiary to themselves.

Financial Aid Impact

Grandparent-owned 529 plans are not reported as an asset on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA).

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, simplified the FAFSA starting with the 2023-24 FAFSA (subsequently delayed until the 2024-25 FAFSA by the U.S. Department of Education). Among other changes, the simplified FAFSA drops the cash support question, so distributions will no longer count as untaxed income to the beneficiary on the beneficiary’s FAFSA.

This will eliminate any impact from a grandparent-owned 529 plan on federal student aid eligibility starting with distributions in 2022. This, of course, assumes that there are no further delays in implementation of the simplified FAFSA.

Leaving A Legacy

Grandparents can open a 529 plan for each grandchild. If the grandparents have three children and nine grandchildren, they could open a total of twelve 529 plans, one for each child and grandchild.

With 5-year gift-tax averaging, they could make lump-sum contributions totaling $1.8 million as a couple (e.g., $150,000 per beneficiary x 12 beneficiaries = $1.8 million). This yields a significant reduction in the grandparents’ taxable estate. Grandparents can also use a 529 plan to hint that they’d like their grandchildren to go to college.

529 plans are a great way of leaving a legacy for your heirs. If there is leftover money in the 529 plan after paying for college, the unused funds can continue to grow and be passed on to future generations.

Leftover money can also be used for other expenses by making a non-qualified distribution. But the earnings portion of the non-qualified distribution will be subject to ordinary income taxes and a tax penalty as opposed to estate and inheritance taxes.

Major 529 Plan Policy Changes Are Unlikely

Policymakers are unlikely to limit the use of a 529 plan for estate planning. When President Obama proposed taxing 529 plans in 2015, his proposal was met with fierce opposition from both Democrats and Republicans. In fact, the resistance was so hostile and swift that he was forced to drop the proposal just a few days later.

Lifetime Exemption For Federal Gift Taxes

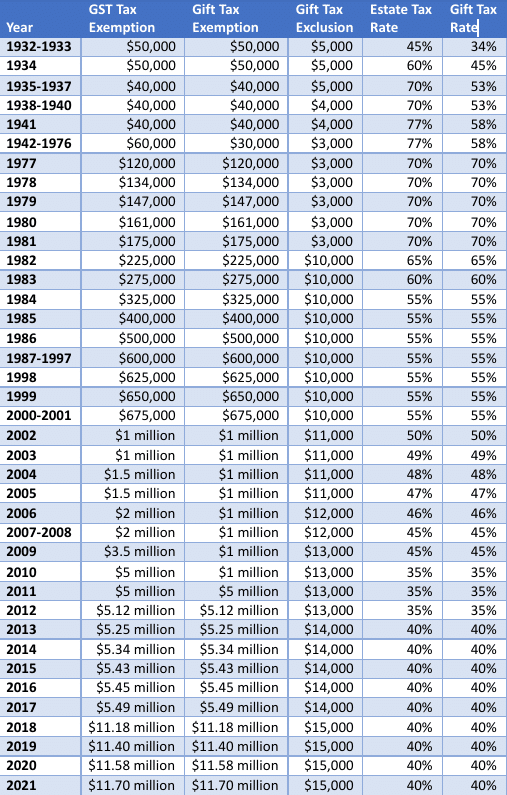

This table below shows the changes in the lifetime exemption for federal gift, estate and generation-skipping transfer taxes over the last nine decades. Key changes were made by the following pieces of legislation:

Who Should Consider 529 Plans For Estate Planning?

If grandparents are close to the lifetime exclusions or are worried about future cuts in the lifetime exclusions, they should consider using 529 plans for estate planning.

529 plans are particularly useful when the grandparents are wealthy but the parents are not. The favorable financial aid treatment of 529 plans lets grandparents who are wealthy help pay for elementary, secondary and postsecondary education expenses without affecting the grandchild’s eligibility for need-based financial aid.

Mark Kantrowitz is an expert on student financial aid, scholarships, 529 plans, and student loans. He has been quoted in more than 10,000 newspaper and magazine articles about college admissions and financial aid. Mark has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Reuters, USA Today, MarketWatch, Money Magazine, Forbes, Newsweek, and Time. You can find his work on Student Aid Policy here.

Mark is the author of five bestselling books about scholarships and financial aid and holds seven patents. Mark serves on the editorial board of the Journal of Student Financial Aid, the editorial advisory board of Bottom Line/Personal, and is a member of the board of trustees of the Center for Excellence in Education. He previously served as a member of the board of directors of the National Scholarship Providers Association. Mark has two Bachelor’s degrees in mathematics and philosophy from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and a Master’s degree in computer science from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU).

Editor: Robert Farrington Reviewed by: Chris Muller